The Free University Berlin was established during the Berlin Blockade by a group of students and scholars on December 4, 1948. With American support, this university located in West Berlin was born out of necessity. It was established as a de-facto successor to East Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University (Humboldt University of Berlin), which had grown increasingly repressed by Communist forces. The University’s name itself is a nod to Cold War tensions, referring to West Berlin’s status as part of the “free world” as opposed to the “unfree” East Berlin and other areas under Communist control. The United States viewed the establishment of a democratic academic institution in West Berlin, free from “the intellectual vacuum of National Socialism,” as a challenge to communist forces and their repressive political and ideological chokehold on Friedrich Wilhelm University.[1]

With most of Berlin still lying in ruin following the war, it was proposed that an entirely new campus be constructed to house the Free University. Dahlem, a residential district in southwest Berlin, was selected as the site of the new campus. The proposed site was formerly part of the Domäne (crown lands). 120 hectares of this land was previously allocated for the relocation of facilities from Friedrich Wilhelm University, however, this arrangement fell through due to Germany entering the First World War and never regained momentum during the interwar period.[2] A 1911 land use plan by Hermann Jansen stated that this site was to be developed as a university campus following American models.[3] Following the Second World War, this land was made available to the Free University Berlin. Classes were held in facilities previously built on the Domäne site by Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft (present-day Max Planck Society), as well as several villas rented around the site. Between 1952 and 1954, several buildings were constructed to house an auditorium and a library.[4]

The Orchard Site Competition

A design competition was held to generate ideas for the new campus. “The Development of the Orchard Site of the Free University Berlin” was announced on March 1, 1963 and invited all West German architects to participate in addition to the thirteen renowned west European architectural firms. Architects were given six months to prepare their designs, which were required to substantially enlarge the university while creating a center for its widely dispersed buildings. The intention of the competition was to replace the provisional Free University Berlin buildings with a large, unifying urban concept.[5] Of the 128 architects who requested the competition brief, only 35 submitted a proposal prior to the deadline, and 12 were selected for consideration by the jury.[6] The “Orchard Site” competition was named for the lands’ previous life as an experimental orchard [Figure 1]. The building site consisted of 13.6 hectares within an open meadow, bounded by villas, groves of trees, and the exiting Dahlem Museum and chemistry buildings. Program requirements included classroom and faculty spaces for humanities, mathematics, and natural sciences, as well as lecture halls, a cafeteria, and 1800 parking spaces.[7]

Architects George Candilis (1913-1995), Alexy Josic (1921-2011), and Shadrach Woods (1923-1973) won the competition to design the university [Figure 2]. Their Paris based firm, Candilis-Josic-Woods, was established in 1955. Both Candilis and Woods were protégés of Le Corbusier. Woods is typically credited for the work on the Free Berlin project along with Manfred Schiedhelm [Figure 3], a German architect was brought on to the project for his ability to communicate in his native tongue.[8]

The Influence of Le Corbusier can be seen in the Free University Berlin project as well as the work of Candilis-Josic-Woods as a whole. This influence stems from Candilis and Woods time spent working under Le Corbusier’s ABAT (Atelier des Bâtisseurs) from 1948-1951. They also served site supervisors on the Unite d’Habitation project in Marseille. The FU Berlin concept embodies several of Le Corbusier’s “Five Points Towards A New Architecture,” namely the separation of structure from non-supporting elements, use of roof gardens, and its free ground floor plan and free facade. The roots of the mat plan organization employed in the university plan can be seen in Corbusier’s Modulor as well as his concept of the “play of the infill.”[9] These streams of influence were more reciprocal than unilateral, as it has been said that Le Corbusier copied the Free University Berlin plan for the design of his 1965 Venice Hospital.[10]

Intent of Candilis-Josic-Woods Design

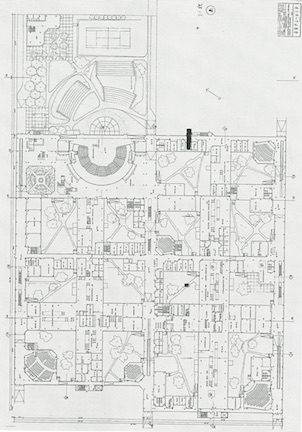

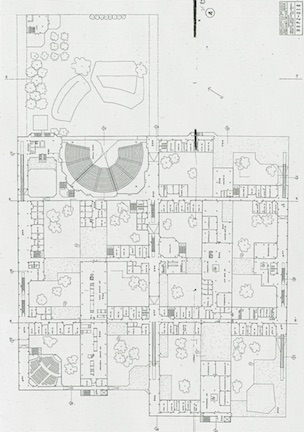

The Free University of Berlin was unique in that it was to be a “universitas litterarum” or a collective university of the humanities and sciences. This ideology was reflected in the winning design by Candilis-Josic-Woods, where university building was transformed into an ideal city, where the academic subjects were in contact with one another to encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. This design reflected a radical rethinking of the education system and became an architectural expression of the artistic and social change emerging during the late 1950s with the onset of the architectural avant-garde movement and attempt to erase the borders between academia and everyday life.[11] The plan of the Free University Berlin integrated the intellectual and the everyday with technological innovation and a concern for society at-large. Emphasis was placed on the flexibility and evolution of the classroom spaces, which were decentralized and distributed within the grid free of hierarchical organization. Following the 1963 competition, the first phase of construction began in 1967 and was completed in 1973. The second phase began in 1973 and completed in 1979. The Candilis-Josic-Woods project is still the largest complex on the Dahlem campus. Affectionately known as the Rostlaube und Silberlaube, roughly translated as the Rust Bucket and Silver Bucket for their choice of cladding materials, these adjacent buildings form one continuous structure organized by an intricate system of internal pathways and courtyards [Figure 4].[12]

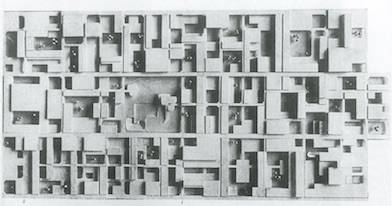

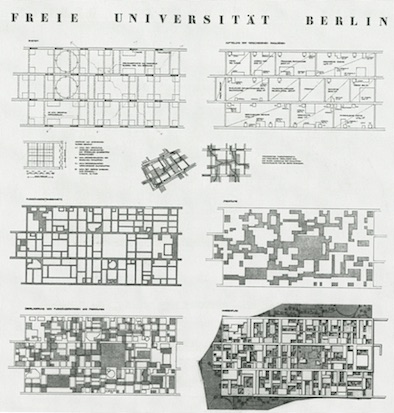

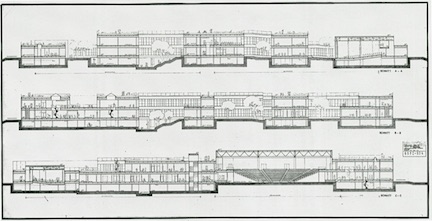

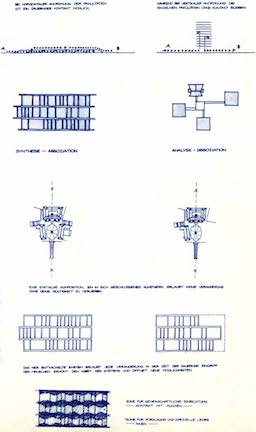

Candilis-Josic-Woods plan for the Free University Berlin was organized in a mat plan arrangement. A mat-building is a large-scale, high-density structure organized on the basis of a modulated grid [Figure 5]. In the Free University, a seemingly regular grid gives general order to the ground plan, however, further analysis of the building in section reveals a more complex layering and shifting of this grid to create the intended condition of interrelatedness between the universities areas of study. The implementation of the mat-building organization dismantled the compositional principles of the early modern period through the use of newly developed architectural strategies.[13]

Due to the complexity of the building, a five-color scheme of red, yellow, green, blue and purple, was used for orientation and wayfinding purposes throughout the building. Interior street signage, featuring a codified numbering system, was also created to orient students and faculty throughout the building. This system consisted of a letter and two numbers, the letter indicating the corresponding main street, the first number represented the side street, and the second number began with the location of the floor (Cellar=0, Ground Floor =1, First Floor=2), and the rest of the digits corresponded to the part of the building, resulting in room numbers that read “L 28 123.”[14] This orientation system required a great deal of explanation, but once understood, it was an appropriate and necessary strategy for finding a room in such a labyrinth of a building.

The competition design for the Free University consisted of a circulation system of internal main streets, which ran parallel to one another at regular intervals throughout the building and extended from floor to ceiling. Side streets were located perpendicular to the main streets and were connected to each other at certain intervals [Figure 6]. Classroom and research spaces were to be located between two main streets and grouped around interior courtyards which were referred to as the lungs of the building.[15] This arrangement created the opportunity for infinite expansion of the building in both length and width. In order to assure that the main streets had sufficient ventilation and daylight, access to the courtyards was given at regular intervals [Figure 7].

This was done through the creation of zones, laid out on a rectangular grid, the dimensions of which were determined by the distance of their centerlines from the main streets. At the ground level, diagonal paths transverse the courtyards to reach the roads, where vertical circulation was located. Sections of the original competition proposal show the architects intent to have large trees inside the courtyards and planted roof terraces to provide exterior spaces for relaxation and instruction[Figure 8].[16]

The implementation of Le Corbusier’s Modulor system can also be seen in the circulation proportions. The side streets were half the width of the main streets, the length of which were 65.63 meters, or roughly the distance the average person could travel in one minute of walking.[17] The circulation system determined the placement of program pieces along the streets and courtyards according to frequency of use. For example, the lecture halls, conference rooms, cafeterias and restrooms were placed in the more privileged spaces along the ground level main streets. Facilities getting less use, such as research spaces, were located along the upper level side streets.

Design Development

The first phase of construction began at the southwestern side of the Orchard Site. This section housed the Institute of German Language and Literature and the Institute of History and lecture halls to support both programs [Figure 9]. With the completion of this building section, we see that the circulation system of streets remains largely unchanged from the competition proposal, however, the distribution of rooms and the courtyards were reconfigured. Candilis-Josic-Woods chose to decrease the amount of divisions to their modulor along the side streets to allow for the insertion of programs such as the library, which were in need of a large continuous area with a single circulation system.[18] As the construction of the Free University continued, it can be seen that the smaller, fragmented spaces proposed in the competition plan were simplified and enlarged in order to create a more clear and regular structure [Figures 10 &11]. The Auditorium Maximum is the largest of the program pieces and sees the most drastic change between the competition and schematic design phases. Originally intended to be a flexible, assembly room for 1330 people, the capacity was reduced to 930 shortly before construction, with an auxiliary assembly room for 400 people sited adjacent to the main auditorium. A straight sliding wall was designed to divide the Auditorium Maximum into two spaces with 533 and 397 seats respectively. The highly complex and flexible hall that was envisioned in the competition design was distilled to a relatively conventional auditorium space at the time of construction.[19]

The appearance of the first building section of the Free University Berlin us attributed to Jean Prouvé. The Rostlaube building got its nickname from its characteristically problematic Cor-Ten steel facade, which he designed.[20] Prouvé’s design for the wall system throughout the building determined the facade construction. The dimensions and heights of the Cor-Ten steel panels were again derived from Le Corbusier’s Modulor. The panels were available in either a solid wall, fixed glazing, operable windows, a door, and a closet. These five panel variations comprised the wall system.

Its four main facades are separately considered. [Figure 12] The southeast facade emphasizes the horizontality of the building, with roof bands that step down to follow the slope of the site. The facade increases from one to two stories one it passes the ramp at the eastern corner of the building. This two-story height continues down of length of the building before changing back to one story in height and wrapping around to the western corner. This change in height reflects the configuration of lecture halls behind this facade. The southwest facade stands in contrast to this pronounced horizontality. Its surface is divided in two, separated by a protruding staircase which marks the middle of the structure. This divided the facade into a one-story section on the left and two-story section on the right, with the one-story portion once again denoting the location of lecture halls within the building. In addition to the facades, the design of the courtyards and roofs were equally considered. The courtyards were articulated through the changes in building height. Roof elements such as skylights or glass stair enclosures as well as planted and paved roof terraces help to create a unique and varied landscape and add interest to the building facades.[21]

Contextualizing Free University Berlin

The end of the 1950s ushered in a spirit of cultural optimism and desire for radical change in the industrialized western world. Out of the lethargy of the post-war period emerged a new generation who looked confidently to the future. This shift in social and political norms led to optimism and blind belief that architecture had the capacity to design communities for a new age.[22] During this period, utopianist beliefs that thoughtfully considered planning and architecture could bring forth not only academically mature but also socially adjusted citizens were popular throughout the architecture and planning profession. Higher education was seen as tool for social reform, and architecture and planning provided the framework. In his book, The Postwar University: Utopianist Campus and College, Stefan Muthesius examines the rhetoric surrounding this post-war focus on educational reform, specifically in West Berlin. He chronicles the utopian planning principles that emerge during the 1950s and 60s, specifically, the idea of designing a campus as a single whole, rather than as a collection of buildings on a particular site [Figure 13]. The Free University Berlin embodies this holistic planning strategy. Its mat building concept dissolves the previous perception of what a university campus should look like and how it should be arranged.

The social, political, and economic circumstances of the post-war era influenced professional discourses on the future of the university campus. University expansion occurred during a positive political and social climate that encouraged such growth. This growth was indicative of the emerging ideas of social welfare and of making higher education accessible for all. In response to ongoing social change, such as the evolution of social norms and student preferences, as well as the proliferation of the personal automobile, the university campus was in the midst of a period of transition. The work of groups such as Team X shows the formal exploration into what these changes could mean for university and campus planning and design as a whole.

Influence of Team X

George Candilis and Shadrach Woods were founding members of the group known as Team X, which emerged in the late 1960s following the demise of CIAM. The group established themselves as the new prophets of modern architecture. Other notable members included Dutchmen Aldo van Eyck and British architects Alison and Peter Smithson. All Team X members were required to be practicing architects and have theoretical views that aligned with the group’s core values. These included a return to the tenets of early modernism and a consideration of contemporary issues facing design. Team X played a pioneering role in exploring the concept of “growth and change” in design, which was also central to the Japanese Metabolist group, a source of inspiration for Shadrach Woods and the Free University Berlin design.[23]

Team X broke from CIAM on ideas such as new monumentality, preferring the ideas of growth, change, and mobility advocated by other popular movements of the time, including De Stijl, Russian constructivism, and the aforementioned Japanese Metabolists. These ideas were applied the design of university buildings through the creation of campuses that serve as extensions of the city itself. In the Free University Berlin, Woods envisioned a city created through human interaction, rather than monuments and axes. The building itself, with its highly internalized circulation, created an environment that fostered this sense of human integration, but the fact that it was an institute of higher learning only heightened the potential to create Woods ideal city. Team X also broke with CIAM on the division of the four functions of working, living, relaxation and transportation. In FU Berlin, the rigid divisions and hierarchies between disciplines were to be eroded through the removal of physical barriers present in typical university buildings of this time. Again, the intention was to better facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration. This furthered Woods’ utopian hopes for the university to become a platform for an equitable and democratic exchange of knowledge to take place.[24]

The debates and discourses during the 1950s and 60s about architecture as an instrument for social change followed two different lines of argument. The first being that architects and urban planners should be the driving forces behind the creation of communities for the new age. This group was blindly optimistic about the capacity of the architect and architecture itself to address the emerging social issues of the day. The second belief was rooted more in the fields of architectural history, sociology, and anthropology and emphasized the inherent logic that characterized the spatial expression of many communities.[25] The tension between these arguments for designing the community can be seen in the work of Team X, specifically in the work of Candilis-Josic-Woods. Shadrach Woods initially published the firms structuring beliefs on urban design in a 1962 article in the avant-garde periodical Le Carré Bleu [Figure 14]. In this essay he spoke of the concept of the web, his refinement of the stem arrangement other Team X members were exploring at the time, as a method in which to approach “a true poetic discovery of architecture.”[26] Unlike the stem, the web arrangement was intended to facilitate multiple connections to discourage isolation. These ideas can be seen in both the design intent and the mat plan arrangement of the Free University Berlin, the form of which can be seen as the culmination of Team X’s research on architectural relations.[27] The mat building form was an intricate weaving of space, circulation, and program into an open framework. At the Free University Berlin, this network of in-between spaces where balconies and rooftops overlooked other spaces for recreation and learning, creates a building which serves as a machine for interdisciplinary study – one of the main goals of Candilis-Josic-Woods’ design.

Conclusion

The Free University Berlin can be studied as an influential example of postwar campus planning as well as an example of the radical shifts in thinking occurring within in the design profession at the time. While the extent to which it successfully functioned as an incubator for interdisciplinary collaboration can be debated, its urban design qualities have been viewed in a positive light. The buildings merit lies in its creation of a dense, urban center that permits infinite expansion as space allows. The buildings system of courtyards and rooftop gardens, which offer relief from the complex and confusing circulation system, are still largely popular with the student body.

These post-war notions of the university and its power to reform can be seen through the goals of Team X and Candilis-Josic-Woods’ design for the Free University Berlin. In postwar Germany, the integration of higher education and the city to create a centralized node for the free the party in power during both Nazi rule and post-war foreign occupation. Through a deeper look into these underlying conditions for this shift in educational practices, we discover how the discourse of groups such as Team X gained traction given the political, social, and economic climate of the time. As this period of utopian optimism faded into the 1970s, so too did the revolutionary ideas of Candilis-Josic-Woods and their design for a new university model. An ideal city that functioned as a machine for the free exchange of knowledge across disciplines.

Bibliography

Anthon, Carl. “The Birth of the Free University.” The American Scholar 24, no. 1 (1954): 49-64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41207913.

Avermaete, Tom. “‘Comment Vivre Ensemble’: Imagining and Designing Community in the Work of Candilis-Josic-Woods.” Building Material, no. 16 (2007): 70-75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29792315.

Calabuig, Debora Domingo, Raúl Castellanos Gomez, and Ana Abalos Ramos. “The Strategies of Mat-building.” Architectural Review. August 13, 2013. Accessed March 1, 2018. https://www.architectural-review.com/rethink/viewpoints/the-strategies-of-mat-building/8651102.article.

Candilis, Josic, and Woods. “PROJECT FOR THE FREE UNIVERSITY OF BERLIN.” Ekistics 18, no. 108 (1964): 369-72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43616710.

Deyong, Sarah. “An Architectural Theory of Relations: Sigfried Giedion and Team X.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 73, no. 2 (2014): 226-47. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.2.226.

Heilmeyer, Florian. Uncube Magazine. July 15, 2015. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.uncubemagazine.com/blog/15799747.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 68, no. 2 (2009): 268-70. doi:10.1525/jsah.2009.68.2.268.

Kiem, Karl. Die Freie Universität Berlin (1967-1973) Hochschulbau, Team-X-Ideale und Tektonische Phantasie: The Free University Berlin (1967-73) Campus design, Team X Ideals and Tectonic Invention. VDG Weimar, 2008.

Krunic, Dina. “The Groundscraper: Candilis-Josic-Woods’ Free University Building, Berlin 1963-1973.” Master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 2011. http://dissertations.umi.com/ucla:10019.

Muthesius, Stefan. The Postwar University: Utopianist Campus and College. Yale University Press, 2000.

Smithson, Alison. ‘How to Recognize and Read Mat-Building. Mainstream Architecture as it has Developed Towards the Mat-Building.’ Architectural Design. September, 1974.

Tzonis, Alexander and Liane Lefaivre. “Beyond Monuments, Beyond Zip-a-tone. Shadrach Woods Berlin Free University, A Humanist Architecture.” Carré Bleu, no 3-4. (Paris, 1998). 4-47.

Woods, Shadrach. Carré Bleu, no 3. (Paris, 1962).

Notes

[1] Karl Kiem, Die Freie Universität Berlin (1967-1973) Hochschulbau, Team-X-Ideale und Tektonische Phantasie: The Free University Berlin (1967-73) Campus design, Team X Ideals and Tectonic Invention, 22.

[2] Kiem, 22.

[3] Kiem, 22, referencing Michael Krauss, “Die Villenuniversität”, in Bauwelt, vol. 69, no. 23, Gütersloh (1978), 862.

[4] Kiem, 22.

[5] Kiem, 22-24.

[6] Kiem, 26.

[7] Kiem, 26.

[8] Kiem, 94-96.

[9] Kiem, 98-102.

[10]Alexander Tzonis, and Liane Lefaivre. “Beyond Monuments, Beyond Zip-a-tone. Shadrach Woods Berlin Free University, A Humanist Architecture,” Carreé Bleu, no 3-4, (Paris, 1998), 39.

[11] Kiem, 12-16.

[12] Kiem, 12.

[13] Debora Domingo Calabuig, Raúl Castellanos Gomez, and Ana Abalos Ramos, “The Strategies of Mat-building.” Architectural Review, August 13, 2013.

[14] Kiem, 68.

[15] Kiem, 52.

[16] Kiem, 54.

[17] Kiem, 52.

[18] Kiem, 56.

[19] Kiem, 60.

[20] Florian Heilmeyer, Uncube Magazine, July 15, 2015.

[21] Kiem, 62.

[22] Tom Avermaete, “‘Comment Vivre Ensemble’: Imagining and Designing Community in the Work of Candilis-Josic-Woods.” Building Material, no. 16 (2007): 70.

[23] Kiem, 114, 130.

[24] Kiem, 124.

[25]Avermaete, 70.

[26] Shadrach Woods, “Web,” Carré Bleu 3 (1962).

[27] Sarah Deyong, “An Architectural Theory of Relations: Sigfried Giedion and Team X.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 73, no. 2 (2014): 238.