The outcome of Mexico’s 1910-1917 revolution was a monumental effort, led by all levels of government and private citizens, to reevaluate and reposition the past. Art and Architecture played a crucial role in this. During the 1920’s and thirties, many government-sponsored painters covered acres of public walls with mythological scenes of Mexico’s pre-Columbian and revolutionary past. These paintings were meant to teach and inspire the general mass public as well as display the governments newly found respect and marriage of historical legitimacy and political progression. “It may in fact be said that the modern Mexican nation was founded on the successive eradication and recovery of the past. And that this was played out in a series of large-scale and profoundly political architectural acts.” 2 With this new interest in the humanities and social sciences a culmination of art and architecture is formed. This referencing of the past spilled over to all art forms, including architecture. Architects took on the responsibility of “cultural leaders and social Technicians”.

An “extraordinary boom” occurred during World War II which altered Mexican national character and identity. These speculations related to Mexico’s now powerful political and economic circumstances. Among these speculations were “the Mexican federal government’s marked shift to the right, the undermining of traditional culture that came with rapid urbanization and industrialization, the pressure the country felt to take sides in international military and diplomatic conflicts, and its need to participate in an increasingly global economy.” 5 This brought up great debates of what it meant to be Mexican in the modern age. What were the proper roles of and relationships between indigenous and imported, popular and elite, present and past?

The National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) is one of the largest universities in the world, with a community of 329,740 people. It owns University City, probably one of the most extended university campuses and one of the largest single tracts of urban property in the world at 1811 Acres.

It is located in the metropolitan area of Mexico City, which has a population of 18,591,527 inhabitants over an area of 360,775 acres.

“The university and Mexico city have shared a long history, involving not only the CU campus but also a wide variety of buildings that the university has owned or occupied in the metropolitan area, currently 126 separate properties on 2962 acres. Many of them have an interesting history in their relations with their immediate surroundings, yet the most fascinating has been the acquisition, development, and transformation of CU, the main campus in the southern part of the metropolis, a long process that started at the beginning of the twentieth century. The CU campus played an important role in the university’s ideal of achieving autonomy. It had a deep impact on the urban structure at the time, triggering speculation and development of different sorts and transforming the land’s potential uses by the end of the century.” 4

The site chosen for the campus is South of Mexico City and held significance due to the ancient Mexicans who once inhabited the site. Architectural remains of this ancient civilization are still present today. University Rector Luis Garrido stated that the University City was “rising in a place marked by destiny. It was the seat of an ancient civilization and now it will be the seat of the culture of the future.” 2 The master plan of the Campus was designed by architects Mario Pani and Enrique del Moral, with contributions from 60 designers including Juan O’Gorman and murals in the main campus painted by some of the most recognized artists in Mexican history such as Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

In heavily referencing the works of Le Corbusier and the Beaux-Arts movement, the Mexican architects avoided historical styles and adopted what they referred to as modern functionalism. With backing from the government, post-revolutionary Mexico was based on a mix of economic and ideological grounds. This required a new functionalist architecture to be cheap and easy to build and maintain. Materials used for these projects consisted of reinforced-concrete (new to the region), brick and glass. This architecture was not based on the past but on the current issues and the potential of the present day. “Noble technological architecture”, said O’Gorman in 1936, “architecture that is the true expression of life and that is also the manifestation of the scientific means of contemporary man.” 4 This functionalist architecture was widely accepted by the Mexican Government and in the rebuilding of the war torn land, much focus was placed on health, education and public works.

These government-backed works showed great promise and the University City campus for the National Autonomous University of Mexico was to be its greatest architectural realization. The architecture and planning of the university intended to accommodate and effect social change and to “define and prepare the new Mexico.” 2 Mexican architects turned to their nation’s past for inspiration and positioned themselves as stewards of Mexican Culture. “The project’s planning, while indebted to the urban planning principles spelled out in CIAM’s Charter of Athens of 1933, also deliberately echoed the terraces, axial, and large, open courts of ancient Mexican Cities such as Monte Alban and Teotihuacán.” 2 While many of the buildings echoed Le Corbusier’s low lying slabs, some referenced pre Columbian Sites. Many others were clad with large-scale murals representing subjects such as “the history of ideas in Mexico or pre-Columbian sport.” 2 According to project manager Carlos Lazo, all of this was to “integrate the individual with the noblest desires of the community. It is here where people would come to absorb the lessons of their nation’s long and glorious past and prepare for an even more brilliant future.” 2 It is here where “the ultimate goals of the Revolution would be attained.” – la Raza Cósmica Education Minister José Vasconcelos. Through these clad murals, the space becomes monument.

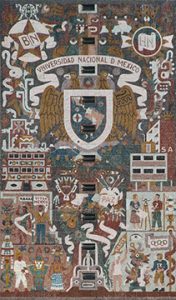

Among these landmark buildings sits the Campuses Central Library. The Library is centrally located on the north side of the campuses main square. In 1948 the architect and painter Juan O’Gorman was invited to the project by fellow architects Gustavo M. Saavedra and Juan Martínez de Velasco. Construction of the UNAM Central Library began in 1950 and the library opened its doors in 1956. Designed by the architect and painter Juan O’Gorman, it’s been classified as a masterpiece of functionalist architecture ever since. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the Central Library collection includes 428,000 volumes in the general collection and another 70,000 in the historical collection. Further archives include collections of printed and similar materials from prior to 1800. “From the beginning, I had the idea of doing mosaics with the colored stones in the blank walls with a technique in which I already had experience. With these mosaics, the library would be different from the rest of the buildings within University City, and it was given a Mexican character,” 5 O’Gorman said. The geometric, box-like design bears murals which represents the different stages of Mexican History.

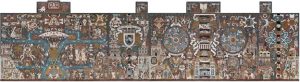

The mural on the north side is divided by a vertical central axis and two transversal axes, marked by blue water currents, which make reference to the Lake character of the ancient capital of the Aztecs. This corresponds to the current historic center of Mexico City.

The East wall, representing The Contemporary World, displays an atom in the center of the new worldview which is the generator of vital energy.

The South wall presents the basics of Spanish thought in that time, marked by the contradiction between God and demon, religiosity and worldliness, as bases of the culture. It offers a vision of the European world in conjunction with the indigenous, and develops the scheme of the colonial world.

The west wall, which is visible from the interstate, represents The University and Modern Mexico. The universities great coat of arms makes reference to the creative and recreational activities of this house of study.

The left side of the wall forwards us to one of the most traditional aspects of the Mexican people; clothing, which is an allusion to the popular and proletarian origin of professors, researchers and students of the University, as well as to the permanence and vitality of our culture. This space aims to reinforce the presence of the University in contemporary Mexico. Through this Mural as well as many others, the artists use complementary oppositions of the reality of Mexico; World labor and Industry opposed to rural traditions.

The National Autonomous University of Mexico is a testimony to the modernization of post-revolutionary Mexico. The City Campus serves as a significant icon of modern urbanism and the progress of humankind through education. Still today, the City Campus is one of very few models where principles proposed by modern architecture and urbanism are applied in totality.

Bibliography

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Central University City Campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma De México (UNAM).” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed April 16, 2018. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1250.

- Eggener, Keith. “Architecture as Revolution: Episodes in the History of Modern Mexico – by Carranza, Luis E.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 31, no. 2 (2012): 273-75.

- Giedion, Sigfried. Architecture, You and Me: The Diary of Development. Harvard U.P;Oxford U.P, 1958.

- Perry, David C., and Wim Wiewel. Global Universities and Urban Development: Case Studies and Analysis. Cambridge, Mass: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2008.

- Ross, Clif, Marcy Rein, and Raúl Zibechi. Until the Rulers Obey: Voices from Latin American Social Movements. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2014.