ARC 590: Global Modernisms Research Project – Brandeis University: A Product of Postwar Campus Planning

Seth Barnett | Professor Burak Erdim | May 07, 2018

Introduction

The research topic chosen for this seminar course focuses on Brandeis University. Undergoing this task has led me to findings beyond the university’s core values and statement made through the establishment of such an institution of higher education and to the role this institution had played in the early development of the Postwar Campus design.

Establishment of Brandeis University

The beginning of this exploration occurs prior to the establishment of Brandeis University. In the year 1946 the property for the future university was acquired from the former Middlesex University in Waltham, Massachusetts, and consisted of a rural landscape of farmland and wild marshes dotted with several small and oddly-shaped buildings. The inheritance included several structures from an old farm, and others from the ill-fated Middlesex medical school[1] (Figure 2). Brandeis University was then founded in 1948 as a nonsectarian university by the American Jewish community at a time when Jews and other ethnic and racial minorities, and women, faced discrimination in higher education.[2] By being a nonsectarian university that welcomes students, teachers and staff of every nationality, religion and orientation, Brandeis renews the American heritage of cultural diversity and equal access to opportunity and freedom of expression. The university’s Diversity Statement was therefore established in 1948 as a model of ethnic and religious pluralism. In addition to this point, the core of Brandeis is animated by a set of values that are rooted in Jewish history and experience. “The first of these is a reverence for learning. Brandeis reflects the values of the Jewish community by pursuing rigorous academic work of the highest standards. Second is an emphasis on critical thinking, including self-criticism. At Brandeis, students and faculty are encouraged to question openly and accept nothing without study, debate and reflection. Third is the Jewish ideal of making the world a better place through one’s actions and talents.”[3]

Figure 1: Brandeis University’s Insignia. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. Back Cover)

Figure 2: Aerial photo of Brandeis University’s existing site upon acquisition of acreage, previously Middlesex University. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.3)

Naming the University

The strength of these values is even laid into the naming of the university. The university was named for Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis (Figure 3), the first Jewish justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Brandeis was one of the greatest minds to serve on the high court, Justice Brandeis made an indelible mark on modern jurisprudence by shaping free speech, the right to privacy and the rights of ordinary citizens. He exemplified the values of the new university through his dedication to open inquiry and the pursuit of truth, insistence on critical thinking, and his commitment to helping the common man.[4]

Figure 3: Portrait of Justice Louis Brandeis, the man Brandeis University is named after. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.1)

Brandeis Master Plan

Such a strong need for a model of ethnic and religious pluralism called for a new campus masterplan designed to fit these student’s needs as well as the university’s. Under the leadership of founding president Abram L. Sachar, it was decided that a Master Plan was an important priority for the new university. This decision followed the university’s experience of a housing crisis within a year of its foundation. In 1950, the University Administrators hired the well-known firm of Eero Saarinen, of Saarinen & Associates, to plan the campus.[5] The choice of Eero Saarinen, an internationally recognized proponent of the modern movement in architecture, set an important precedent for the development of the school. Although Saarinen’s involvement with Brandeis was brief (from 1950-1952), he left an imprint on the growth of the campus.

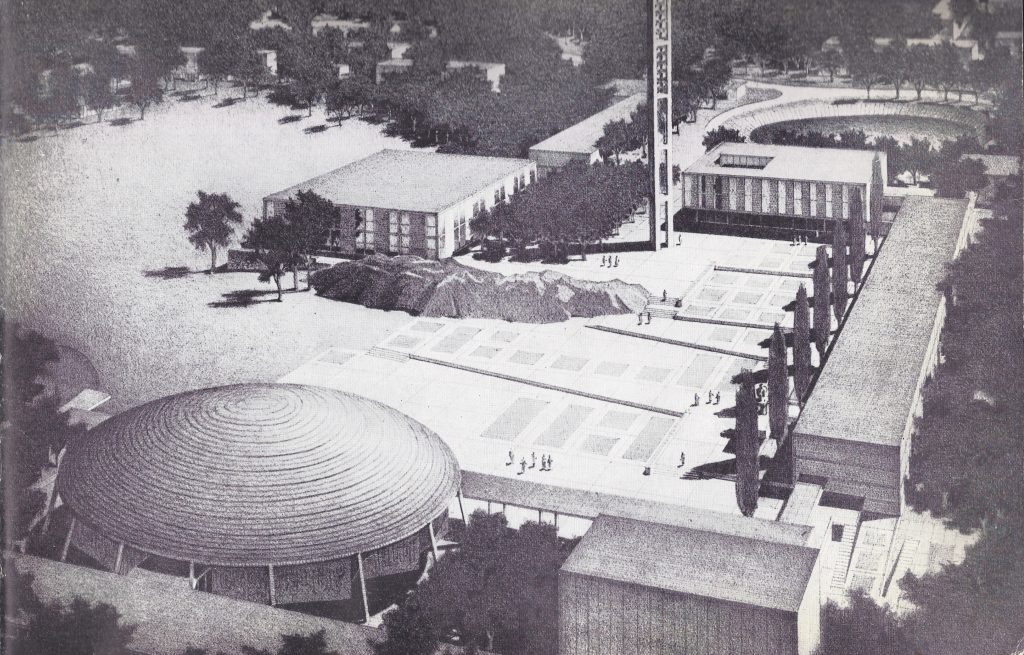

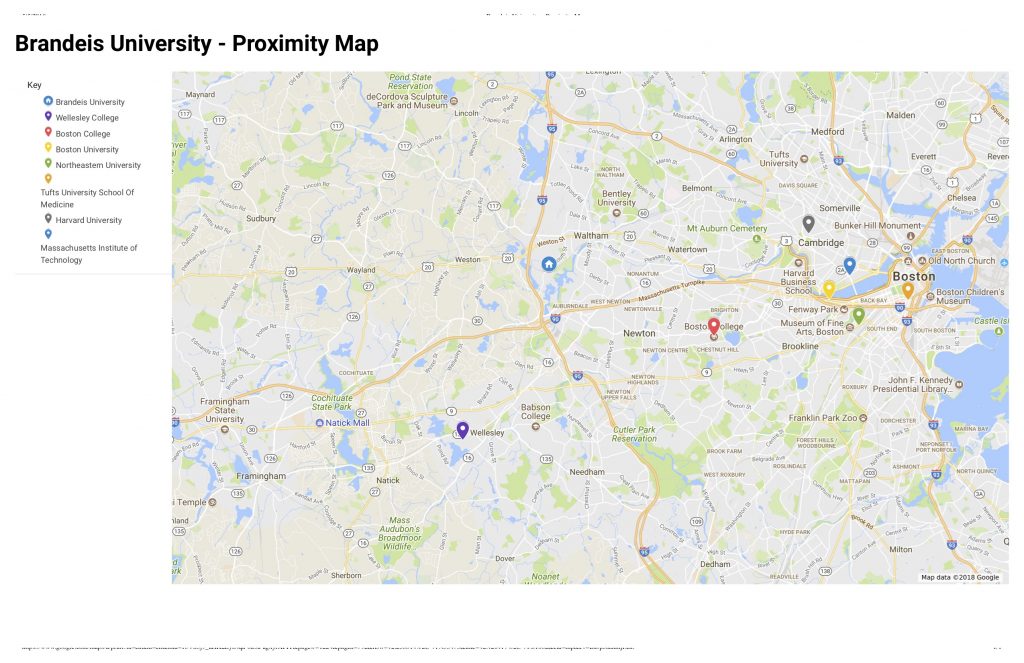

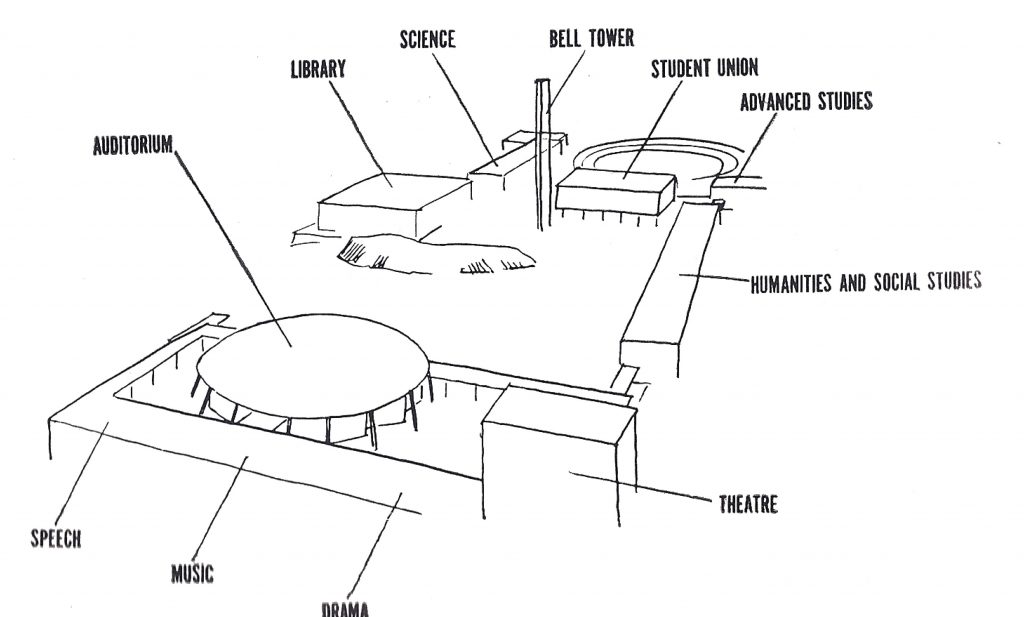

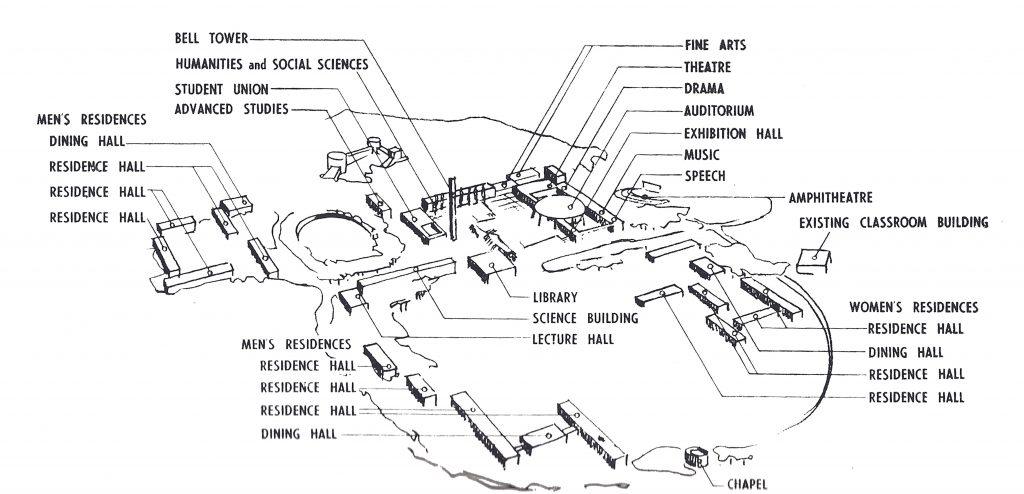

Eero Saarinen collaborated with Matthew Nowicki in creation of the masterplan for Brandeis University. This proposal is contained within a publication produced by the University that was designed for the interest of alumni/donors, titled A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University. This document describes the design of the masterplan as a “seat of learning” (Figure 4) and further provides drawings produced by Saarinen and Nowicki that illustrate each building component required in the masterplan to meet the ideology of Justice Brandeis as well as the University’s in creating a campus designed for the ethnic and religious pluralism embedded within the diversity statement designed for equality for all people no matter their religion, race, or gender. The last portion of this publication includes a visionary section for the future campus and reads:“To leave a moment to posterity – and to create a link between the present, past, and future – is a rare privilege given to those who build a university.”[6] Such a strong prevalent nature for Brandeis University, who was looking to create a new model for institutions of higher education in an area of multiple notable universities within the immediate area (Figure 5).

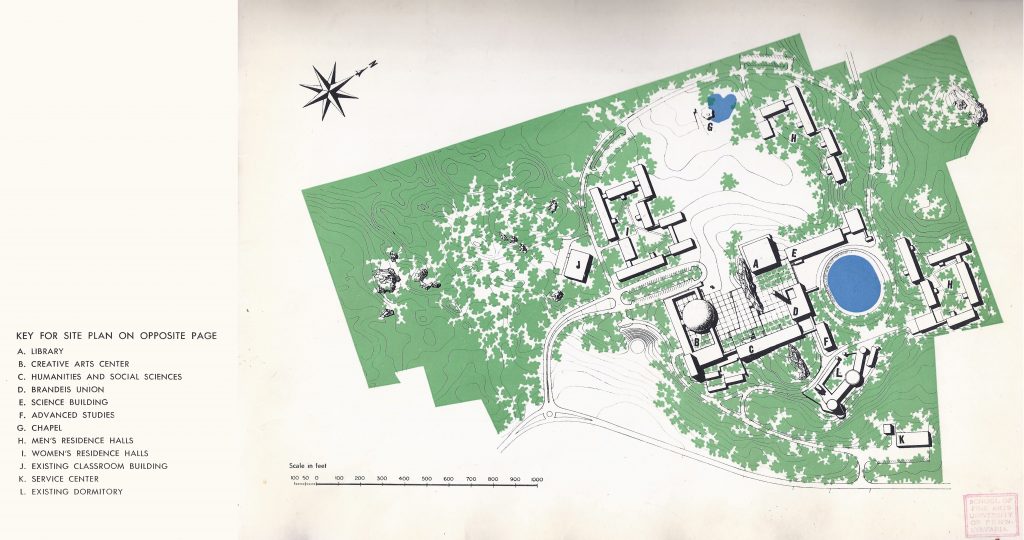

An in-depth analysis of the initial masterplan prepared by Saarinen & Associates for Brandeis University in the 1950s composed of three main elements: The core (referred to as “The Seat of Learning”), the Residences, and the Chapel. The masterplan (Figure 6) included two existing buildings, a residence hall and a classroom, to remain as part of the developing campus, as these were buildings inherited from the former Middlesex University when Brandeis University took ownership of the land. The following breakdown of these elements proposed are derived directly from the University’s publication of the masterplan titled, A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University.

Figure 4: Rendering of Brandeis University’s Core from Saarinen’s Masterplan. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.7)

Figure 5: Current day map of surrounding prominent universities. (Source: Google Images, https://www.google.com/maps)

Figure 6: Site Plan proposal for Brandeis University from Saarinen’s Masterplan. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.5)

The Core: The Seat of Learning

The core of the campus masterplan is referred to in the publication as a “seat of learning” (Figure 7), and reads:

“The heart of the university is the college quadrangle around which are located the University Library, Brandeis Union, the new Science Building, the Humanities and Social Science Building, the Theatre, the Art and Music studios, and the striking University Auditorium. It is here that Brandeis University will fulfill the prophetic vision of the Justice Brandeis’ ideal of a great university: It must become truly a seat of learning where research is pursued, books written, and the creative instinct aroused, encouraged, and developed in its faculty and students. “[7]

Figure 7: “The Seat of Learning.” (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.6)

The Seat of Learning: The Library

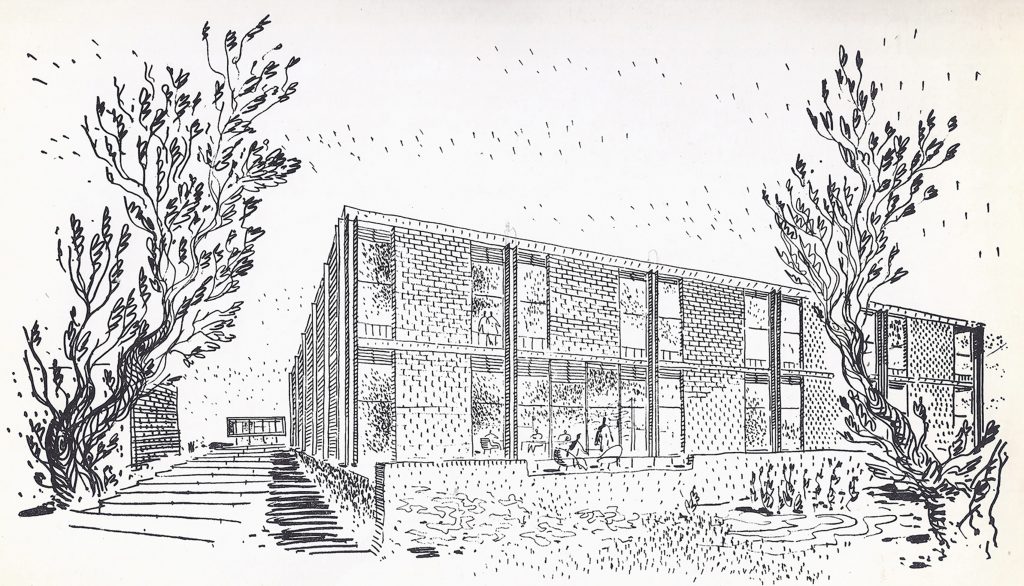

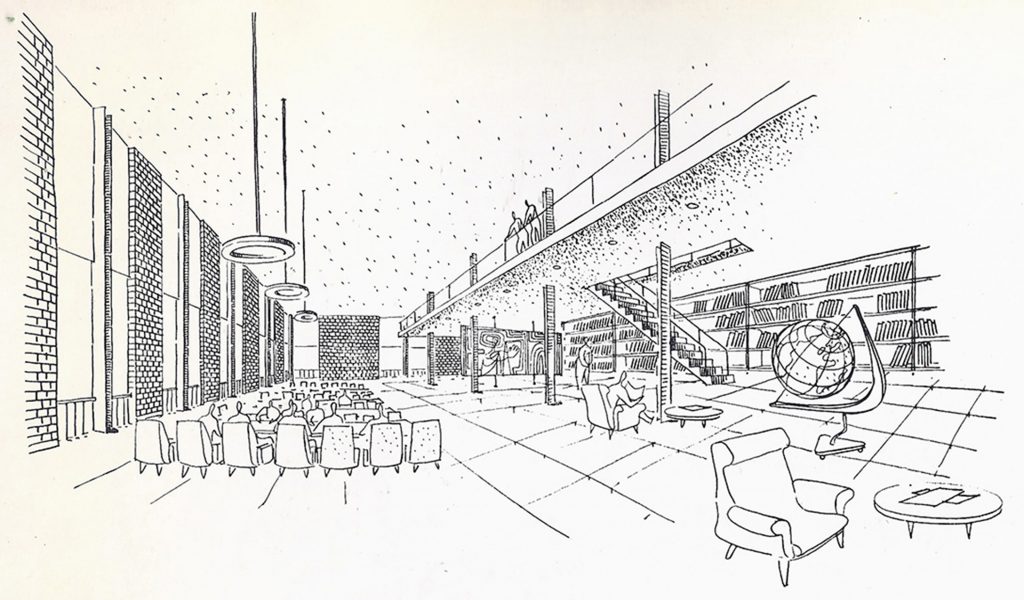

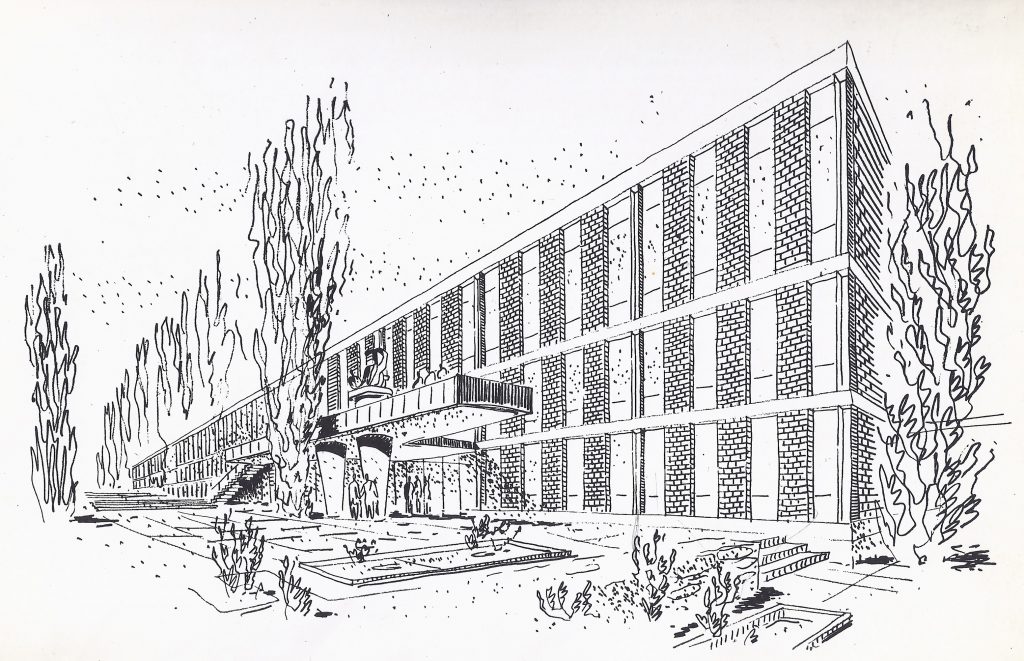

The first of these members to explore is the University Library (Figures 8 and 9). The publication proposes that “the richness of a Library is a measure of the University’s academic resources.”[8] With such a statement, the design proposal includes programmatic elements of the Library to consist of individual reading halls devoted to the Humanities, Social Sciences, Natural Sciences, Law and Medicine. The Library program is to include a rare book room, multiple alcoves, seminar rooms, as well as special rooms designed for microfilm and audio-visual purposes.

Figure 8: The University Library Exterior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 9)

Figure 9: The University Library Interior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 8)

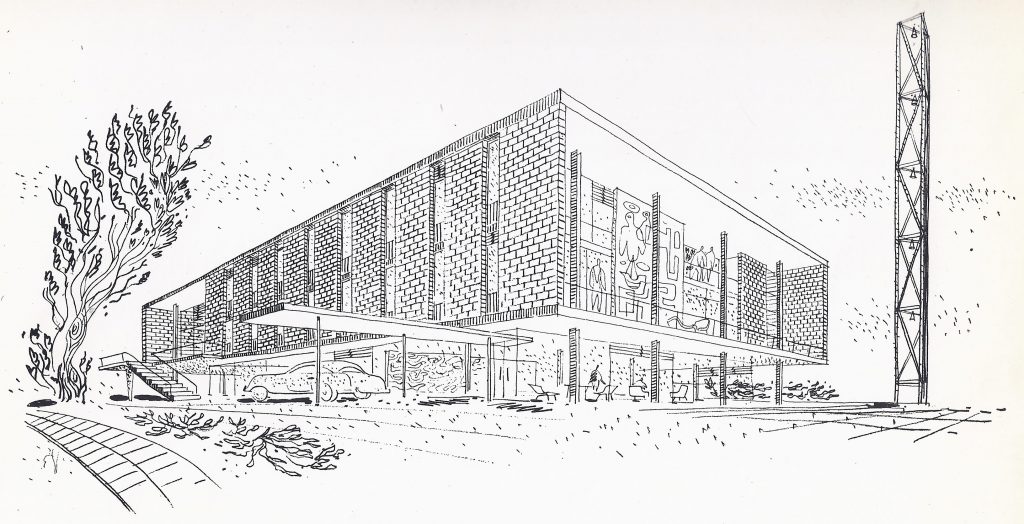

The Seat of Learning: Brandeis Union

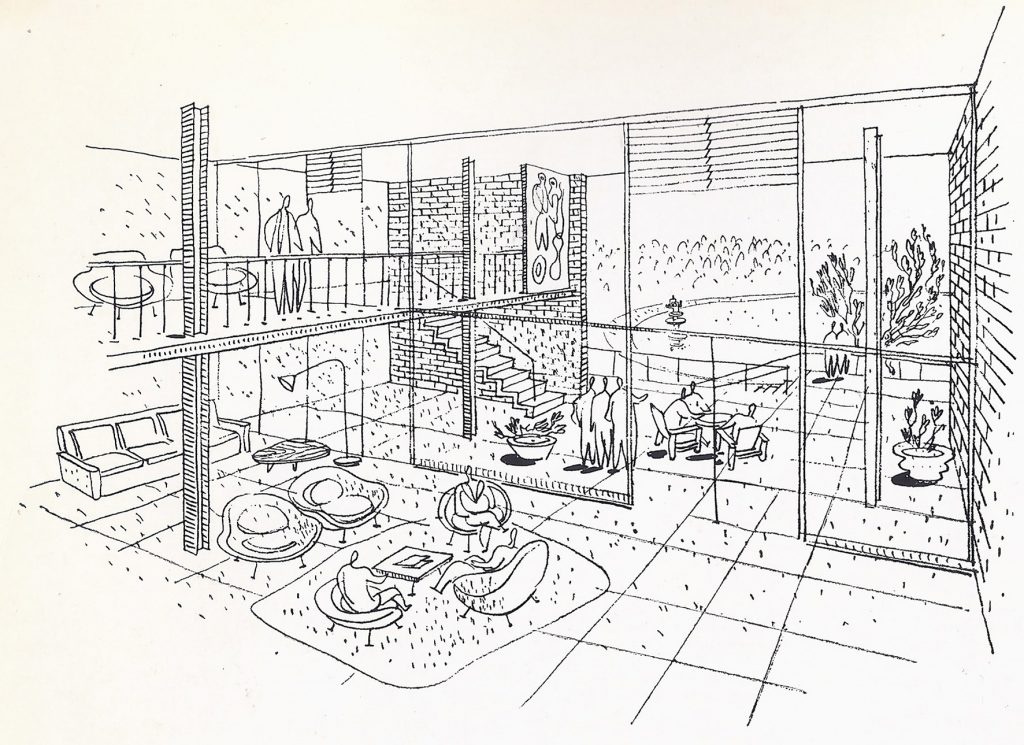

The social member, Brandeis Union (Figures 10 and 11), is designed to focus on providing a hub for student organizations. This building program is devised to satisfy the varied recreational and social demands of young people.[9] In being the hub for student life, the building is intended to reflect the tempo, vitality and range of student life.[10] The physical program for the building includes social lounges for men and women, a hobby room, cafeteria, snack bar, ballroom, alumni headquarters, and guest rooms. Such proposed programmatic elements are designed to ensure that the Student Union will be the social center for the entire Brandeis community in creating a meeting place for students, faculty, alumni, guests, and friends of the University.[11]

Figure 10: The Brandeis Union and Bell Tower Exterior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 11)

Figure 11: The Brandeis Union Interior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 10)

The Seat of Learning: Humanities and Social Sciences

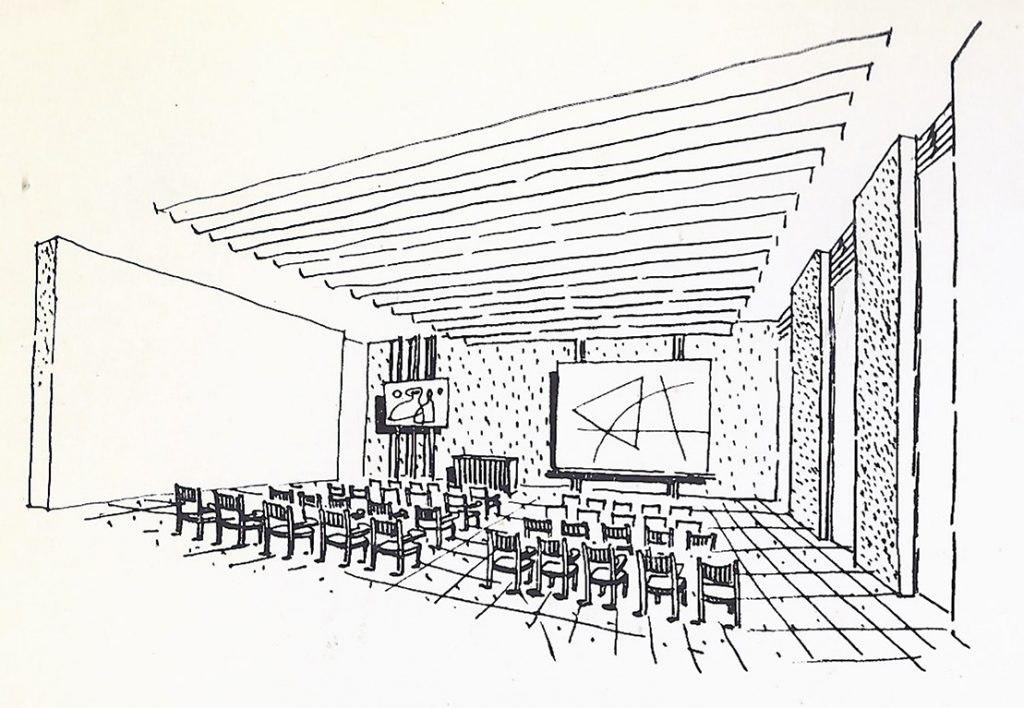

The liberal arts member, Humanities and Social Sciences (Figures 12 and 13) is included within the masterplan to strengthen the vitally important work of its field’s research and instruction. Saarinen & Associates have included this important programmatic element within their proposal in response to the recent experience of American Universities neglecting the need for the humanities and social sciences due to the increase of attraction of benefactors towards the scientific areas.[12]

Figure 12: The Humanities and Social Sciences Exterior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 13)

Figure 13: The Humanities and Social Sciences Interior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 12)

The Seat of Learning: The Sciences

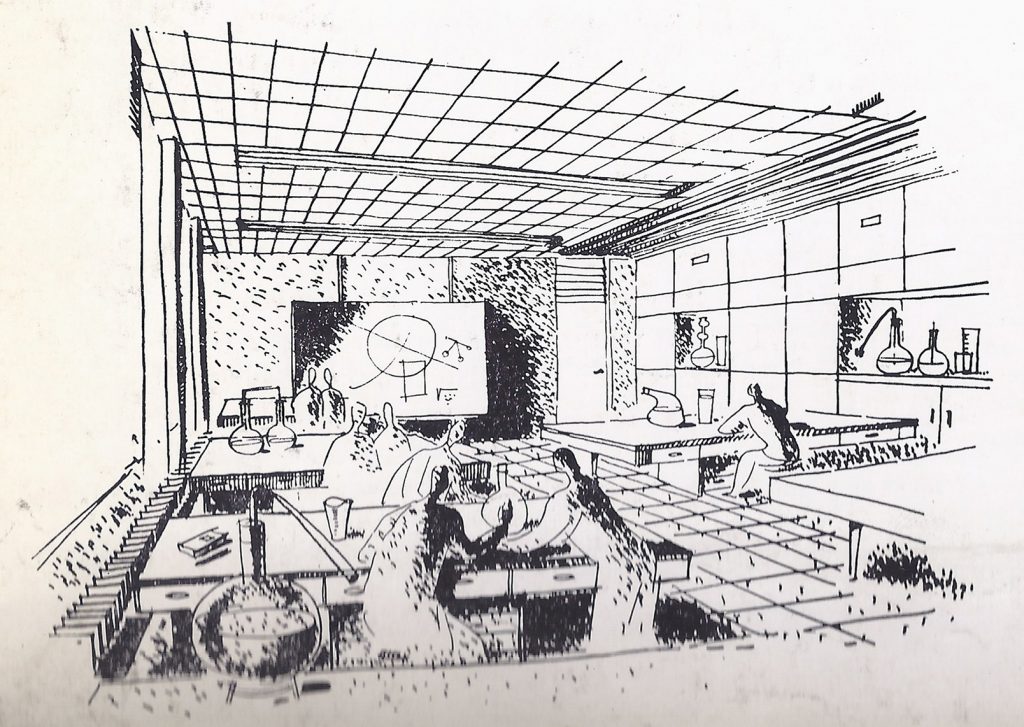

The Sciences member of the core is proposed as a special building format designed for flexibility (Figures 14 and 15). In their proposal, Saarinen & Associates make the point that beyond introductory instruction of the sciences, the field has complicated a modern university’s requirement for the areas to achieve advanced instruction and further opportunities in research.[13] Therefore, “if Brandeis is to assume responsibility for training future scientists, it will require a building sufficiently flexible to keep abreast of the expanding frontiers in biology, physics, chemistry, and other sciences”[14] The goal then is to provide a building platform that allows for a diversity of programs to use the space in each of their own field’s unique method of operating a laboratory. Such diversity at this scale of program is similar to the University’s design to achieve pluralism.

Figure 14: The Sciences Exterior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 15)

Figure 15: The Sciences Interior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 14)

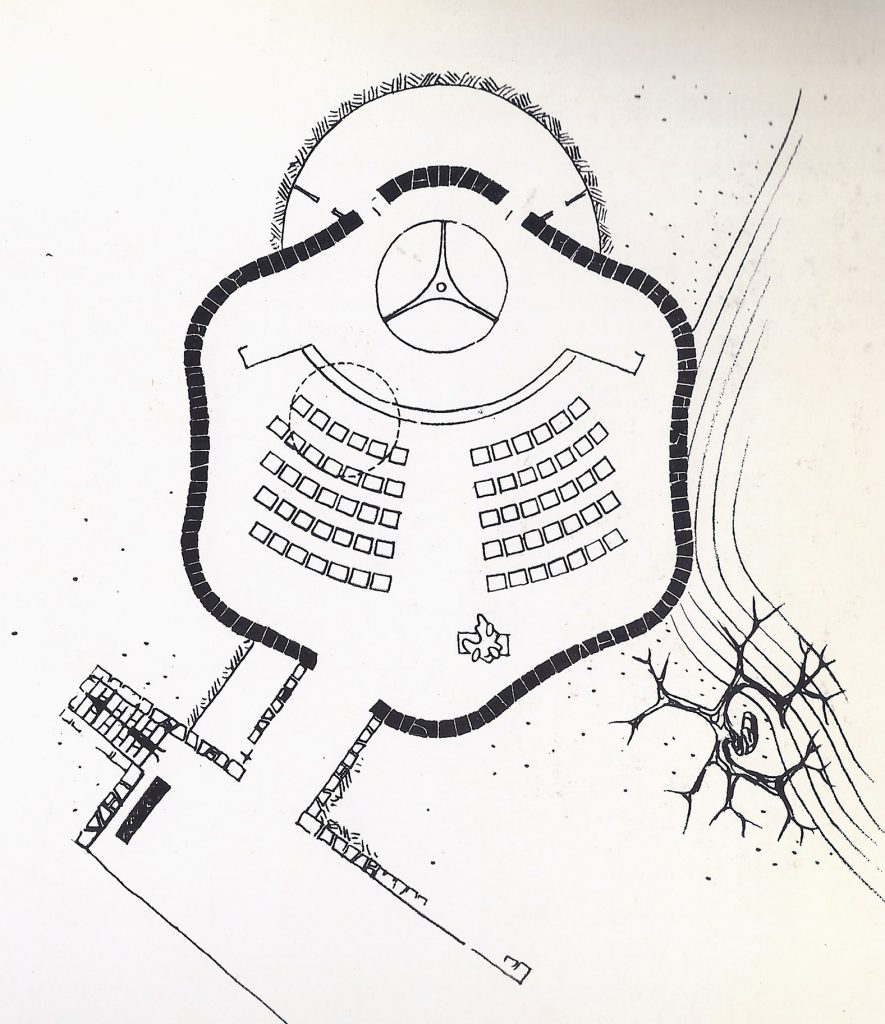

The Seat of Learning: The Creative Arts Center

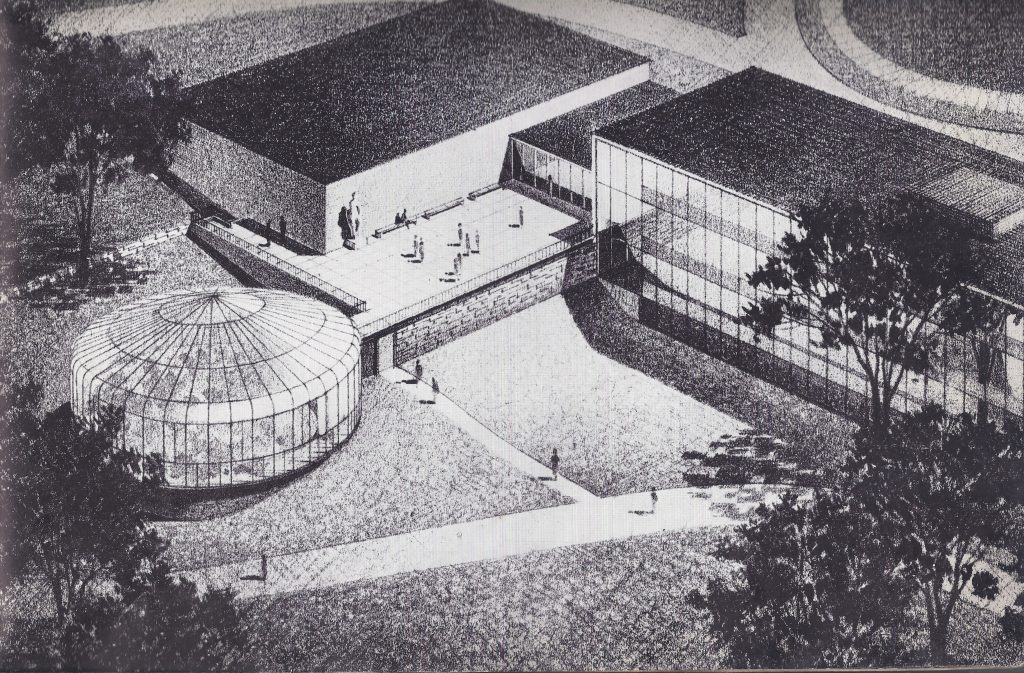

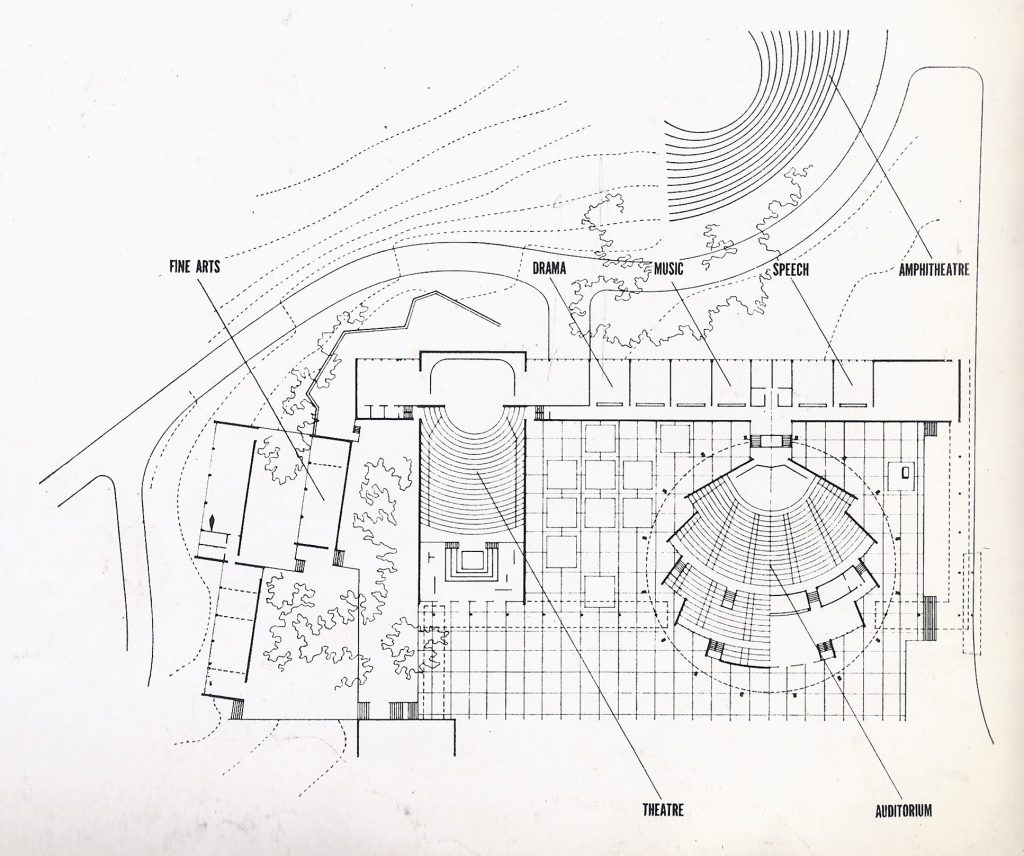

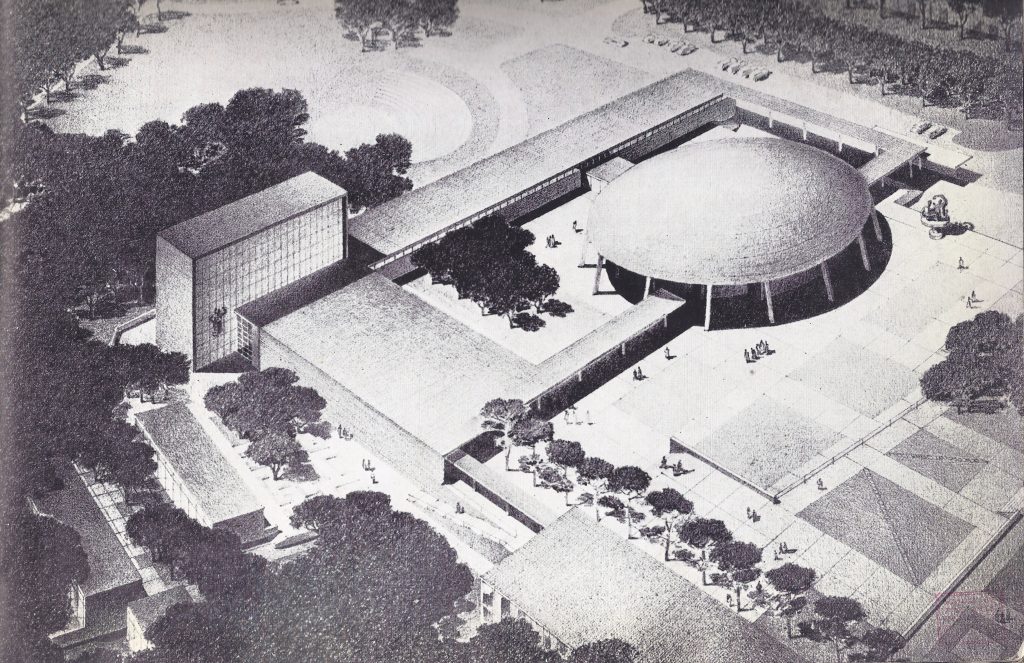

The last member of the core is the Creative Arts Center (Figures 16 and 17). This member is an essential piece of the University in order to move with the times in the provision of instruction in Music, Drama, Fine Arts, and Speech. Similar to the Sciences, each of these departments will require special facilities to adapt to each one’s functionality. To provide for greater integration and exchange of experience, the three programs are planned to be housed close together and have therefore been linked together architecturally. The classrooms, studio, and theatre are designed to connect with the auditorium in order to “attain a physical unity that will focus on the aesthetic impact of the arts.”[15] The auditorium is a bold conception designed to blend its exciting beauty with acoustic perfection.[16] The building’s central location and size make it a convenient meeting place for the entire Brandeis Community, in establishing another node on campus.

Figure 16: The Seat of Learning: The Creative Arts Center Plan (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.16)

Figure 17: The Seat of Learning: The Creative Arts Center Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.17)

The Residence Halls

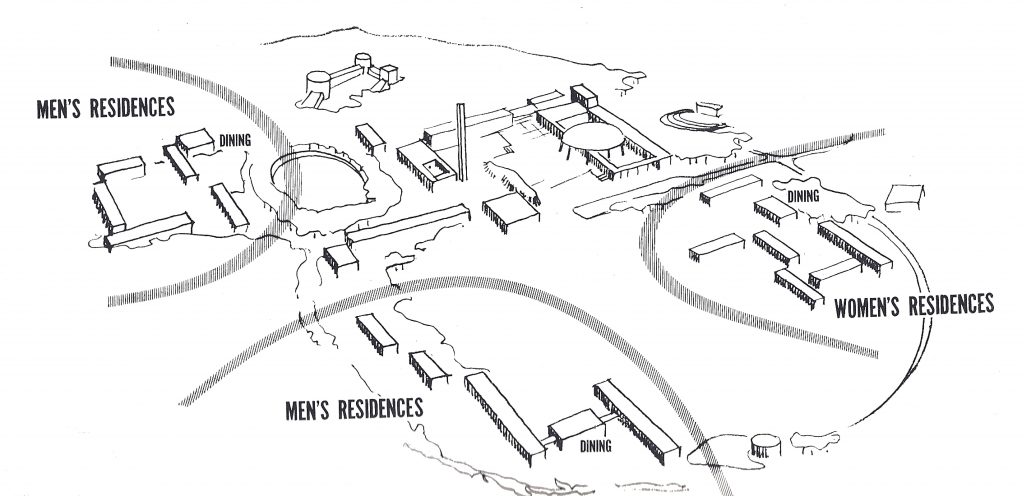

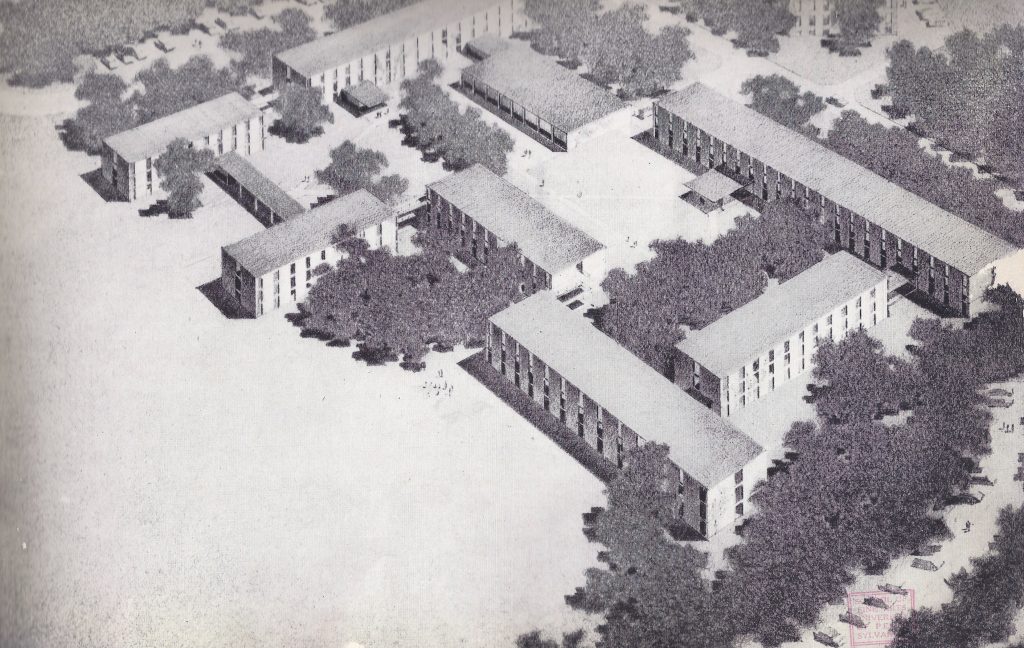

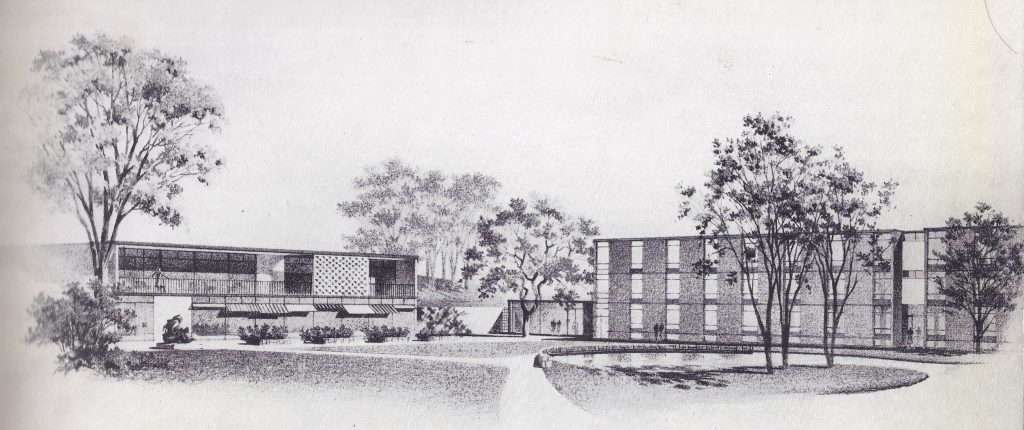

In moving beyond the core of the campus design lies in the next concentric ring, the Residence Halls (Figure 18). “The fundamental aim of the Brandeis housing plan is to establish new opportunities for rich social experience and thus help develop social maturity.”[17] Therefore within the publication the residence halls are defined to be designed as “living quarters” and not “dormitories”. The building proposals then consists of “groupings of small units in an irregular quadrangle to permit a sense of intimacy without losing a feeling of the relationship to the larger whole”[18] (Figure 19). The women’s quadrangle (Figure 20) specifically states that “they will provide proper conditions for living, for study and for social development.”[19] The size of these units is described as an intimate atmosphere for developing the enduring companionship and friendships which will long remain in the memory of the students, as each unit is designed to house seventy-two students.[20]

Figure 18: The Residence Halls. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.22)

Figure 19: Men’s Residence Hall (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.23)

Figure 20: The Women’s Quadrangle (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.25)

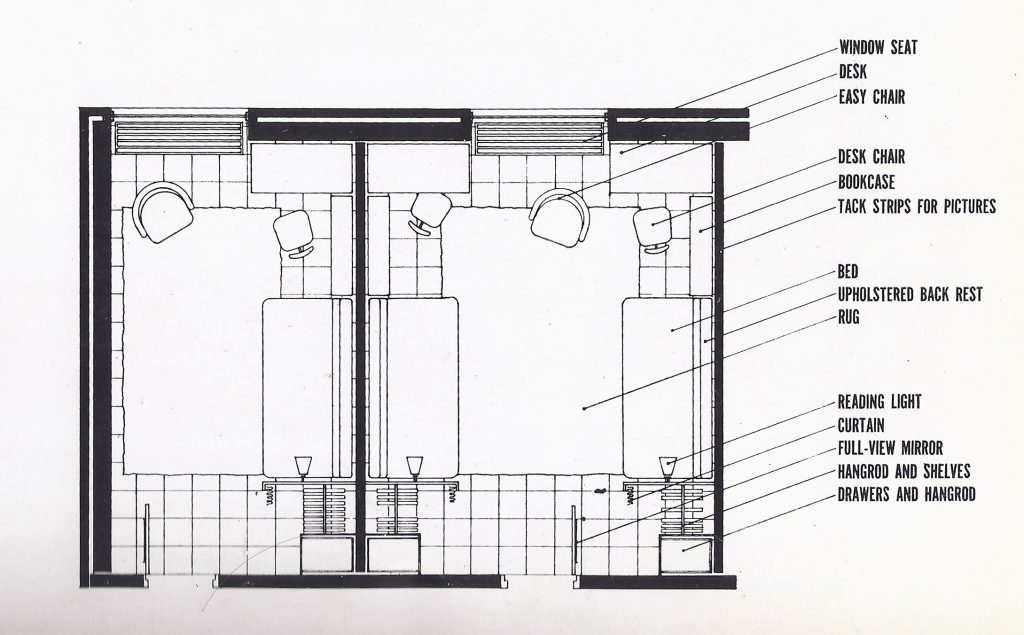

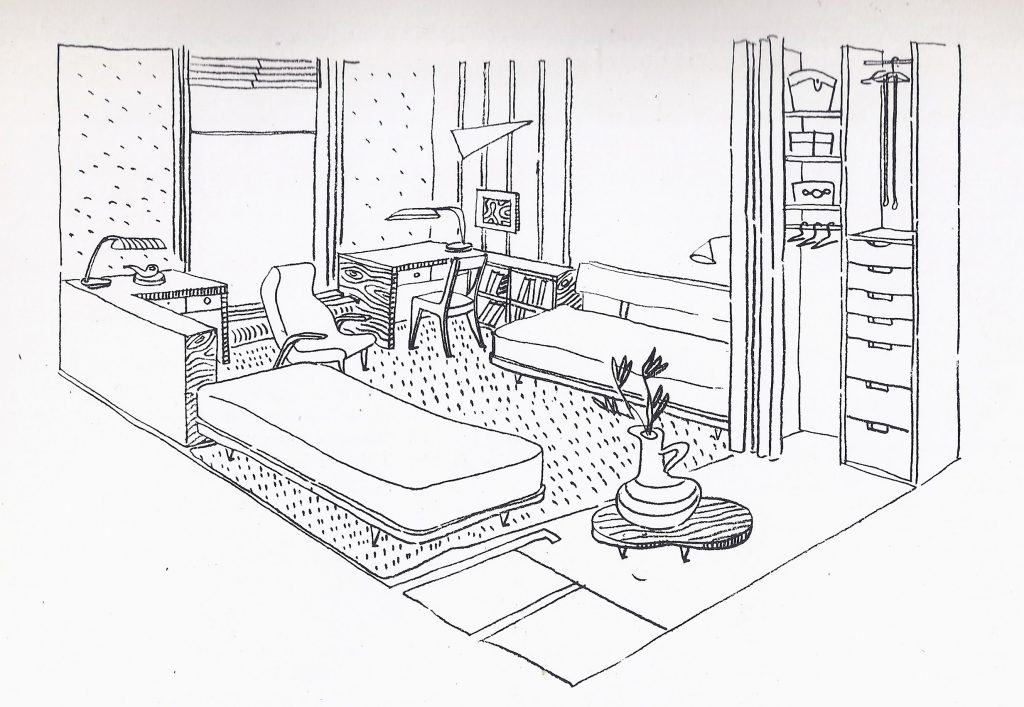

A Student Room

These living quarters designed to generate an intimate atmosphere have therefore received generous thought, as the masterplan proposal includes a section designated for a student room (Figures 21 and 22). The publication includes a floor plan of a student room design with all aspects considered to be desired in fitting a student’s needs, while maintaining efficient use of floor space. The flowing excerpt from the Masterplan publication describes the design of a student room:

“The proposed rooms will be a valuable contribution to the personal life of each student. Comfort and ideal privacy are achieved in attractive quarters while flexibility is demonstrated by the ease with which the bedroom can be converted into a pleasant sitting room. These living quarters will provide a proper setting for the fundamentally important educational aims of attaining individual resourcefulness and social maturity.”[21]

Figure 21: A Student Room Floor Plan (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 28)

Figure 22: A Student Room Interior Rendering (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 29)

The Chapel

The last element of the Masterplan is the Chapel. This programmatic element is placed directly across from the core but exists along the opposite edge of campus, furthest from the core (Figure 23). This piece of the campus is designed to meet the goals of the campus’ core values to create a university that demonstrates the model for ethnic and religious pluralism that was engrained in the conception of freedom in establishment of the United States of America. In reflection of these values of religious freedom, the Chapel was conceived as design intended for the blending of Judaism, Protestantism, and Catholicism faiths within one shared space. This design concept however was not an easy feat to achieve and produced a development over three concepts and between two Architects. Eero Saarinen developed the first (Figure 24) and second scheme (Figure 25), each being rejected by the University. “His first design was a circular, amoeba-like structure containing one altar with light pouring down from overhead. This design was not approved, but Saarinen later built an attractive chapel very similar to this design on the campus of M.I.T. Saarinen’s second design was a three-pronged structure that accommodated separate altars and seating areas for Catholics, Protestants, and Jews.”[22] The chapel design process sparked tremendous controversy among religious leaders as well as students. Some community religious leaders rejected the sharing of space with other denominations, while Brandeis students protested an alternate plan for a single Jewish chapel, in advocating for an interdenominational structure.[23] The third concept was produced by Max Abramovitz in 1956 (Figure 26). Abramovitz’s design called for three separate chapels representing the Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant faiths. The structures were to be equal in size and physically placed so as never to cast shadows on one another and included a heart-shaped reservoir in the center, bringing a natural element to the design.[24] The building design was awarded the American Institute of Architects Award of Merit in 1956, and to this day the Three Chapels remain an architectural gem on the Brandeis campus.

Figure 23: The Future Campus. (Source: Brandeis University, “A Foundation For Learning…,” p.32)

Figure 24: The Chapel – Eero Saarinen’s Scheme 1 (Source: Brandeis University,“A Foundation For Learning…,” p. 31)

Figure 25: The Chapel – Eero Saarinen’s Scheme 2 (Source: Brandeis University, “Building Brandeis: Style And Function Of A University”)

Figure 26: The Three Chapels: Berlin Chapel (Jewish), Bethlehem Chapel (Catholic), and Harlan Chapel (Protestant); Designed by Max Abramovitz. (Source: Harvard University, “Postwar Judaism”)

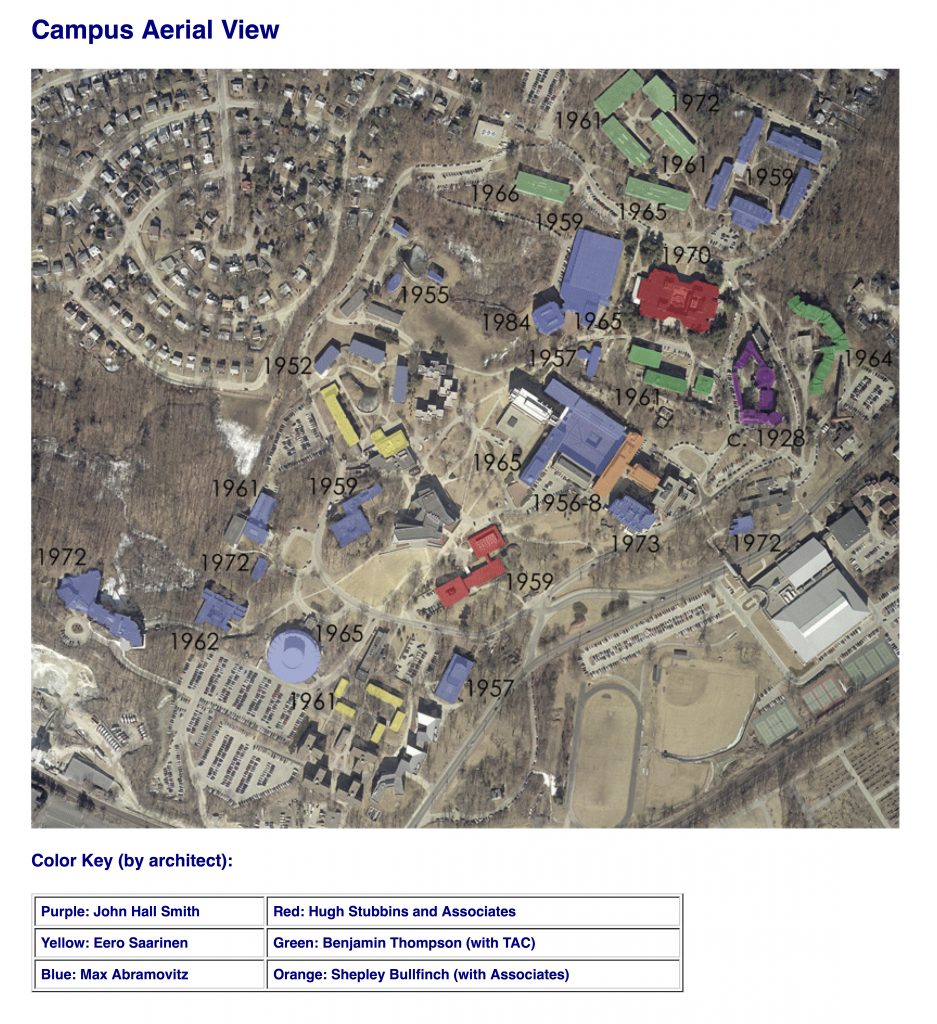

Max Abramovitz’s Leadership in University Planning

Max Abramovitz was responsible for overseeing the University planning for the next 30 years and designed the vast majority of buildings on the Brandeis campus. It is also important to note that Abramovitz was a good friend and former student of President Abram Sachar, as well as being Sachar’s first choice for the masterplan for Brandeis prior to Saarinen’s selection. Abramovitz developed several versions of a master plan for Brandeis, the first of which was produced in 1959. He wanted to create a distinctive architectural identity for Brandeis and utilized materials that complimented the New England environment: red brick, fieldstone, and glass. Eero Saarinen’s involvement with the master plan project and execution for Brandeis was brief with his leave in 1952, by which time four of his building designs had been built. According to information provided from Bernstein’s, Building a Campus: An Architectural Celebration of Brandeis University’s 50th Anniversary,

“Although the architect [Saarinen] had conceived of a campus built in his personal style, many factors, including construction costs and difficulties in fundraising, made that impossible. Saarinen’s expectations for his Master Plan no longer seemed viable as local architects were awarded the commission for the Shapiro Gym.” [25]

It was around this time, during the mid-1950s, that Max Abramovitz was brought on to develop a new masterplan.

Conclusion

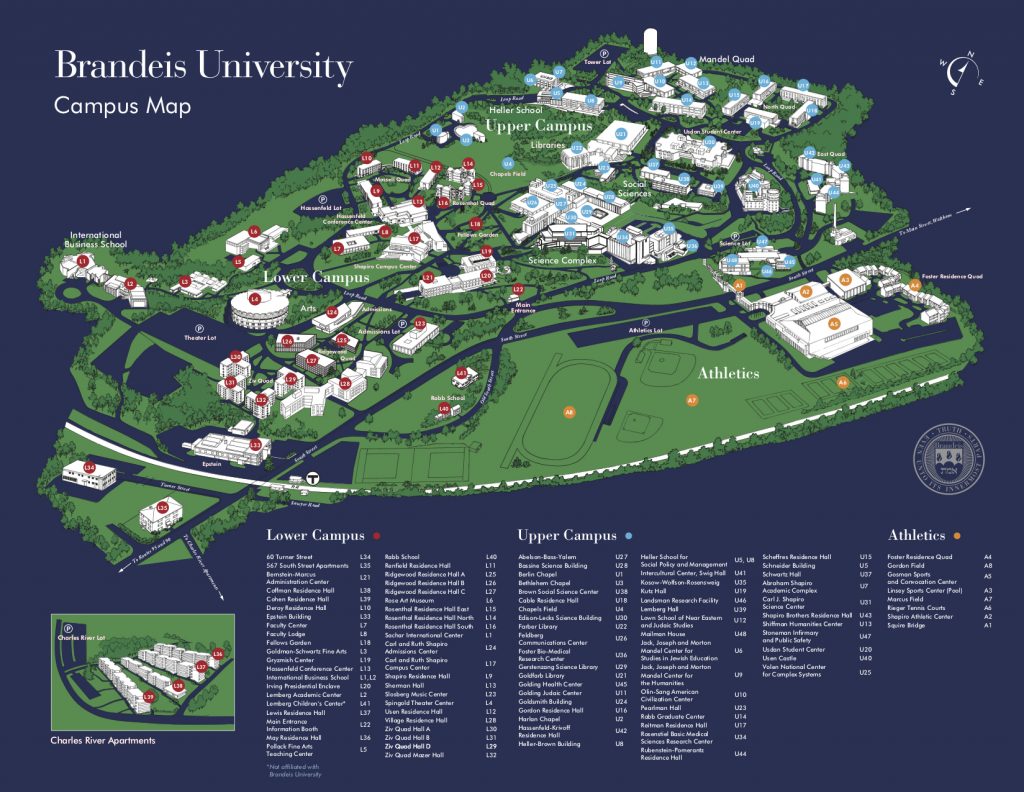

In conclusion, the 1950s masterplan developed by Saarinen & Associates did not achieve full execution but provided a basis of design that forever marked development of the future campus. In the current day Brandeis University map (Figure 27), the centralized core, chapel, and residence halls can all be found in the same areas as proposed in the initial masterplan that had established a guideline of values to follow in maintaining the goals of creating a model university that expressed ethnic and religious pluralism. This map also details how the expansion of the campus appears to follow the same ideals within the publication that new departments and athletic facilities would join the university in further extending the reach of the university’s values to the surrounding community.

In addition to this point, Bernstein’s, Building a Campus: An Architectural Celebration of Brandeis University’s 50th Anniversary, touches on the diversity of the designers involved with the development of the architectural construct of the University, linking Saarinen’s and Abramovitz’s conception of the Brandeis Master Plan to the strong commitment to the basic tenets of the International Style of architecture.[26] Berstein reflects on both architects adoption of the rectilinear, flat-roofed glass box, which in the years following World War II was regarded as cutting-edge modernism, as well as the architectural feature of Brandeis to include the number of architects who were commissioned to work on campus.[27] “Abramovitz, during his tenure as Sachar’s “architectural counsel,” made a concerted effort to bring a variety of architects to the University (Figure 28). From the steel and glass structures of the science buildings by Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson, and Abbot to Benjamin Thompson’s award-winning designs for the Academic Complex, dozens of architects have contributed to the Brandeis experience.”[28] Such a collaborative effort achieved serves as an example of the diversity described within University’s core values in defining a new campus model.

Figure 27: Brandeis University’s Current Campus Map. (Source: Brandeis University, “Campus Map”)

Figure 28: Campus aerial view of the current campus, displaying the Architects involved with each building and years of completed construction. (Source: Brandeis University, “Building Brandeis: Style And Function Of A University,” p.32)

Bibliography

Brandeis University, “Building Brandeis: Style And Function Of A University”. Brandeis University. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://lts.brandeis.edu/research/archives-speccoll/exhibits/building/Intro.html.

Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950).

Brandeis University, “Our Story”. Brandeis University. Last modified 2018. Accessed March 6, 2018. http://www.brandeis.edu/about/history.html.

Bernstein, Gerald S., ed. Building a Campus: An Architectural Celebration of Brandeis

University’s 50th Anniversary. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1999.

End Notes

[1] Brandeis University, “Building Brandeis: Style And Function Of A University”. Brandeis University. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://lts.brandeis.edu/research/archives-speccoll/exhibits/building/Intro.html.

[2] Brandeis University, “Our Story”. Brandeis University. Last modified 2018. Accessed March 6, 2018. http://www.brandeis.edu/about/history.html.

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Brandeis University, “Building Brandeis: Style And Function Of A University”. Brandeis University. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://lts.brandeis.edu/research/archives-speccoll/exhibits/building/Intro.html.

[6] Ibid

[7] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 6.

[8] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 8.

[9] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 10.

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 12.

[13] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 14.

[14] Ibid

[15] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 16.

[16] Ibid

[17] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950). pg 22.

[18] Ibid

[19] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950), pg 24.

[20] Ibid

[21] Brandeis University, Office of University Planning. A Foundation For Learning: Planning the Campus of Brandeis University (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1950). pg 28.

[22] Brandeis University, “Building Brandeis: Style And Function Of A University”. Brandeis University. Accessed March 6, 2018. https://lts.brandeis.edu/research/archives-speccoll/exhibits/building/Intro.html.

[23] Ibid

[24] Ibid

[25] Bernstein, Gerald S., ed. Building a Campus: An Architectural Celebration of Brandeis

University’s 50th Anniversary. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 1999.

[26] Ibid

[27] Ibid

[28] Ibid